In part 1 and part 2, we enforced views for all the stages of fetching data on the front-end.

One thing we need to cover for the app to resemble the benefits of an Elm app is decoding.

After discovering how well decoding works in TypeScript, I almost feel dirty when not using it.

Validating what comes in

We do server side validation on web forms. Why shouldn't the front-end validate what comes in from the backend?

Elm actually forces you to do that, and it contributes to eliminating pretty much all runtime exceptions. When something doesn't check out, it fails fast and loud.

TypeScript lacks this feature as it only type checks what happens in the source code. The interfaces you are writing are strictly speaking just qualified guesses of what you will recieve.

If the api changes without you knowing, TypeScript wont't help you.

A library like Purify or fp-ts can give you these guarantees with little extra effort.

Purify the chaos

In this final part of this series, we will use Purify for decoding. It has lately become my favourite library for TypeScript. It's a pretty simple library that gives us a few utilities and functional data structures, and does a great job of it.

fp-ts is the main contender. It does much of the same but seemingly crams all features of Haskell or Scala into TypeScript. It's a powerful library, but I think Purify is a more pragmatic choice, and easier to learn.

- Use the CodeSandbox from the previous post as a starter code

Make a decoder and get a type for free

In the initial code, we have an interface of the Post type looking like this:

interface Post {

id: string;

title: string;

body: string;

}

Delete it. Wait, what?

As mentioned, it does not help us in type checking external data. And a puny TypeScript type guard is too weak to withstand the chaos outside your source code.

So let's install Purify

yarn install purify-ts

and import the needed dependencies from Codec in index.ts

import { Codec, string, array, GetInterface, number } from "purify-ts/Codec";

Did you delete the Post interface yet? If not, do it now!

Then define this constant:

const Post = Codec.interface({

id: string,

title: string,

body: string,

});

This gives you the decoder. You can extract it into a TypeScript interface just by adding this line below it:

type Post = GetInterface<typeof Post>;

Yes, the const and the type are both named Post 🤔. No worries, there are no naming conflicts. TypeScript is smart enough to understand when to use a type and when to use a value.

Also add these lines right below. This makes a list type so you can validate all the Posts in one operation:

const PostList = array(Post);

type PostList = GetInterface<typeof PostList>;

Replace all occurrences of Post[] with PostList in the code.

Making a type safe fetch request

Now, we only need to modify the fetchPosts function a bit.

async function fetchPosts(): Promise<RemoteData<Error, PostList>> {

const response = await fetch("https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/posts");

try {

if (!response.ok) throw await response.json();

const data = await response.json();

const decodedPosts = PostList.decode(data);

return decodedPosts.caseOf({

Left: (err) =>

({ type: "FAILURE", error: Error(err) } as RemoteData<Error, PostList>),

Right: (successData) => {

return { type: "SUCCESS", data: successData } as RemoteData<

Error,

PostList

>;

},

});

} catch (e) {

return { type: "FAILURE", error: e };

}

}

The decode function typechecks the data argument every time the app fetches the data.

Don't worry if you don't get it all at first. In my opinion, this is best learned by practical use.

The PostList.decode function takes in the uncertain data value from the outside and finds out if the types checks out. It returns an Either value which only can return one of the two values:

- Left: A container with an error message if the types aren't right

- Right: A container with the correct and verified PostList value.

The caseOf function extracts the values out of the Either container.

If it doesn't fail, the data inside the app is now guaranteed to have the correct types.

The convention in functional programming is that the left side argument is the error and right side is right. Right is right.

Let's put it to the test

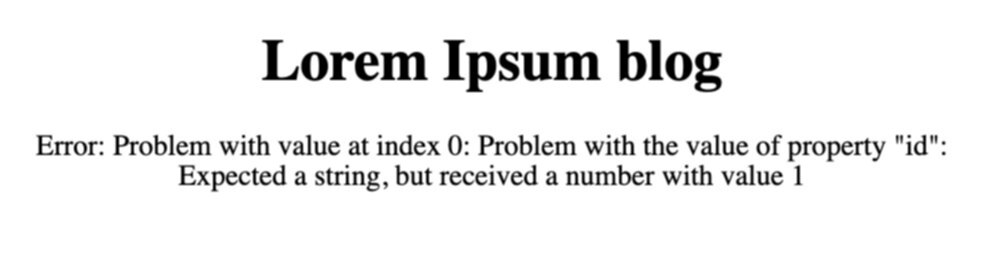

By running your code or this CodeSandbox you can see the result:

What 😱 Who wrote that nice error message??

The decoder of course, and it gives you a helpful error message pretty much like Elm would in this situation.

I have been deceiving you all along. It turns out the id value never was a string after all, even though we declared it as a string already in the very first part of this series.

TypeScript didn't help you catch that. Purify did.

Let's turn the id into a number in the Codec, and we should be all good:

const Post = Codec.interface({

id: number,

title: string,

body: string,

});

- See the complete code on CodeSandbox

What remains

Another improvement to resemble the language features of Elm in React is immutable state. A low barrier entry solution is to use the useImmer hook instead of useState.

Easy Peasy supports immutability by default with redux and Redux DevTools under the hood.

Another alternative is xState. I haven't explored it in-depth yet, but I understand it forces you to be very explicit about what states are possible. Sounds awesome!

These tools have good documentations and large communities, so I won't cover the usage of them in this series.

But to get the full benefits and power of Elm on your front-end, it's still best to use Elm. You can try it out on a small component in your React app and decide wether you like it or not.